Archive for the ‘Stress’ Category

Office of the Future?

Judging by the media attention, our recent British Medical Journal: Occupational Environmental Medicine study (Casey Lindberg et al. & GSA’s “Wellbuilt for Wellbeing” Team, 2018) clearly struck a chord. It seems that workers – at least those who commented online, viscerally hate their open office settings. But what we found, using objective measures collected from wearable devices, was that office workers in open office settings were 32% more active than those in private offices, 20% more active than those in cubicles, and the more active workers were less stressed during after work hours. Such differences, especially when cumulative over a working lifetime, are well within the medically relevant range. A 2018 report summarizing ten studies’ research findings of more than 17,000 people (American Journal of Preventive Medicine) found that simply replacing 30 minutes of sedentary activity daily with 30 minutes of even mild activity significantly reduced BMI (Body Mass Index = weight/height), risk of diabetes, cardiovascular disease and all-cause mortality. Imagine – your office could be part of your daily exercise regime – without any effort at all on your part. And yet people complain of noise, distraction, feeling watched. Indeed, other studies using different measures have reported negative effects (Philosophical Transacations of the Royal Society B). The open offices we studied were designed purposefully to give workers many choices for different kinds of work activities, including quiet areas for individuals, private conversations or small meetings. Although, without more research, we won’t know the reasons, it may be that people in the open offices moved more in order to get to those different spaces. We are entering a new era, where fewer people need to go to an office to work. More are telecommuting, working from home, or wherever they happen to be – coffee shops, the beach. Indeed, at an upcoming summit “RETHINK: Office of the Future: New York“, where I will be speaking, building owners and industry leaders will be grappling with how to design offices to adapt and stay ahead of the times. So, employers, if you want to keep your workers healthy, work with experts to get the objective measures you need to design your offices thoughtfully. In the meantime, workers, you can think of your office as your new gym!

Judging by the media attention, our recent British Medical Journal: Occupational Environmental Medicine study (Casey Lindberg et al. & GSA’s “Wellbuilt for Wellbeing” Team, 2018) clearly struck a chord. It seems that workers – at least those who commented online, viscerally hate their open office settings. But what we found, using objective measures collected from wearable devices, was that office workers in open office settings were 32% more active than those in private offices, 20% more active than those in cubicles, and the more active workers were less stressed during after work hours. Such differences, especially when cumulative over a working lifetime, are well within the medically relevant range. A 2018 report summarizing ten studies’ research findings of more than 17,000 people (American Journal of Preventive Medicine) found that simply replacing 30 minutes of sedentary activity daily with 30 minutes of even mild activity significantly reduced BMI (Body Mass Index = weight/height), risk of diabetes, cardiovascular disease and all-cause mortality. Imagine – your office could be part of your daily exercise regime – without any effort at all on your part. And yet people complain of noise, distraction, feeling watched. Indeed, other studies using different measures have reported negative effects (Philosophical Transacations of the Royal Society B). The open offices we studied were designed purposefully to give workers many choices for different kinds of work activities, including quiet areas for individuals, private conversations or small meetings. Although, without more research, we won’t know the reasons, it may be that people in the open offices moved more in order to get to those different spaces. We are entering a new era, where fewer people need to go to an office to work. More are telecommuting, working from home, or wherever they happen to be – coffee shops, the beach. Indeed, at an upcoming summit “RETHINK: Office of the Future: New York“, where I will be speaking, building owners and industry leaders will be grappling with how to design offices to adapt and stay ahead of the times. So, employers, if you want to keep your workers healthy, work with experts to get the objective measures you need to design your offices thoughtfully. In the meantime, workers, you can think of your office as your new gym!Life Saving Part 2

After my talk, we sat around the table, as I caught up on dinner. I recounted the time in the mid-nineties when I had met Dr. Heimlich at a reception on Capitol Hill. When my host pointed him out to me at the reception, and asked if I wanted to meet him, I had responded “But I thought he was dead.” She said “No. He’s standing over there drinking a martini. Want me to introduce you?” I said of course. We walked over to a tall, elegant man, I estimated then in his late 70’s or 80’s. I asked him if he was really THE Dr. Heimlich. He said yes. Then I asked him how he had figured it out. He smiled, and put his arm around my waist in a fake Heimlich, and said: “By putting my arm around beautiful young women.” Some women had been offended when I told that story, so I stopped telling it. But he did it in such a charming and harmless fashion, that I wasn’t offended at all. I simply laughed and said “No really. How did you figure it out?” He then proceeded to tell me about the years of animal studies he had done as a cardiovascular thoracic surgeon, which led him to figure out the best way to dislodge an object from a choking person’s windpipe. He told me that, more meaningful to him than knowing the tens of thousands of lives that the maneuver had saved, was hearing the individual stories of individual people who had used it to save a loved one. I told him that I had used it on my daughter when she was three years old, when she was choking on a bit of carrot. That was the last time I had done the Heimlich on a real person, until last week when I used it again on my dear friend. How odd that performing a maneuver developed through years of painstaking research, could have brought about in me that ethereal sense of calm. On the one hand, I could explain it by the principles of the stress response. Because of my years of training, my stress response immediately kicked in and gave me the energy to focus my attention and get the job done. My host at the speaking event said as much to me when he observed: “You were like a Labrador – you just shot straight over” and performed the Heimlich. That was my stress response working for me. What about the sense of calm that set in? That was my “relaxation response” kicking in, to counter the stress response and shut it off when it was no longer needed. But I can’t help feeling that it was something more – something or someone watching over both my dear friend and me. We both felt it in the moment: a light, an energy, pouring in from above. When I recounted the story to my sister, she said: “Did you know that Dr. Heimlich just died recently?” [Link] I hadn’t heard. At some level I wonder if maybe Dr. Heimlich knows that I have used his maneuver once again to save a loved one.Good Stress/Bad Stress and Good Relaxation/Bad Relaxation

You’ve heard of “good stress/bad stress,” right? [Link] We’re all probably feeling some of both now, in the holiday crunch.You’re feeling good stress when you are excited about getting together with loved ones, looking forward to sharing gifts, meals, and holiday traditions. Bad stress is feeling overwhelmed by it all, being pressed to get all those gifts bought, wrapped, and distributed in time, while at the same time preparing all that delicious food to serve to your guests, and getting the house in shape too.

The same parts of your brain cause both good and bad stress. The brain’s stress response turns on to give you the energy and focus to get all those things done – that’s the good stress bit. But when the stress response goes into overdrive for too long, that’s bad stress – and it can make you get sick.

What about relaxation – is there “good relaxation” and “bad relaxation”? I believe there is.

Harvard’s Dr. Herbert Benson coined the term the “relaxation response” to describe the brain’s way of countering the stress response. Just as there are brain pathways, hormones, and nerve chemicals that drive the stress response, there is a nerve pathway that underpins the relaxation response. It’s called the vagus nerve.

There are many ways to turn on the vagus nerve and the relaxation response. Most involve deep breathing: meditation, yoga, Tai Chi, gentle exercise, like walking, even prayer. Massage therapy and acupuncture can do it too. These all induce a deep, restorative kind of relaxation, which stops the stress response in its tracks. It’s as if you’re driving down the highway at 90 miles an hour, and you put on the brake – the gas pedal is the stress response and the brake is the relaxation response.

I call all these integrative, mind-body approaches to relaxation “good relaxation.”

But there is also what I call “bad relaxation,” most of which involve prolonged sitting, like couch-potato television viewing, or being glued to your computer screen for hours at a time. There is mounting evidence that prolonged sitting bouts and a sedentary life-style like these, are bad for your health.

So at this hectic time of year, take time out – even just a couple of minutes or so, for some “good relaxation,” especially when you feel like your good stress is turning into bad. Try to avoid “bad relaxation.” Turn off the computer and TV. Instead take a walk with friends, or go outside to toss a football, take a walk, or build a snowman. Or, if you can’t spare the time to relax, try one of Dr. Andrew Weil’s deep breathing exercises [Link] – they take hardly any time at all. You’ll block that bad stress response and shift the anxiety it causes back to where it gives you the energy to enjoy the holidays!

Sidewalk Poem

I came upon this poem, carved into the sidewalk in the most unlikely place – along a six-lane thoroughfare in the Tucson Foothills, overlooking the city and Tucson Mountains to the south, flanked by the Santa Catalina Mountains to the North. I have driven by this spot at least several times per week and sometimes more, from the day I moved to Tucson four and a half years ago. I mostly drive by, like all the other cars, at the speed limit of 45 mph. I slow down if I am turning into my bank’s parking lot at the corner, but I never noticed this poem until today. That’s because the only way to see this poem is to walk over it.

I came upon this poem, carved into the sidewalk in the most unlikely place – along a six-lane thoroughfare in the Tucson Foothills, overlooking the city and Tucson Mountains to the south, flanked by the Santa Catalina Mountains to the North. I have driven by this spot at least several times per week and sometimes more, from the day I moved to Tucson four and a half years ago. I mostly drive by, like all the other cars, at the speed limit of 45 mph. I slow down if I am turning into my bank’s parking lot at the corner, but I never noticed this poem until today. That’s because the only way to see this poem is to walk over it.Yesterday I was forced to walk over it because my car wouldn’t start. I had been rushing about doing holiday shopping and last minute errands, feeling good about myself as I checked off each item on my list. It was well past lunch time, and though hungry, I kept telling myself – just one more thing I need to get, just one more place I need to stop at – then I’ll go home. I had run out of cash so I decided to go to the bank to get cash out of the ATM. I drove into the parking lot, parked, dashed out to the ATM, got the cash, jumped back into the car, set to do just more thing on the list.

I turned the key in the ignition and heard a ticking sound. I turned it again – same thing; and again; and again – but no engine catch. I called my significant other, so he could listen. “Sounds like the battery or something electrical,” he said. “When did you last get a new battery?” I couldn’t remember. “Well, that’s a bad sign,” he said. “Call AAA.”

So I called AAA. They took all my information and said it would take an hour for the service person to arrive – enough time for me to walk across the street to the deli for a sandwich, and be back at the car waiting.

I felt irritated. So much more to do, and now I was stuck. But, then I thought, it was a beautiful, sunny afternoon, I was stopped in a beautiful place, I was safe – things could be a lot worse.

So I started out on my little adventure, heading along the sidewalk to the stoplights at the corner. Cars were whizzing by at top speed – daunting if you are walking along that stretch of road. And then I looked down, and saw the poem. I stopped, turned back and looked at it again.

So I started out on my little adventure, heading along the sidewalk to the stoplights at the corner. Cars were whizzing by at top speed – daunting if you are walking along that stretch of road. And then I looked down, and saw the poem. I stopped, turned back and looked at it again.

I sit still,

The Canyon river chants,

moving mountains.

M.P. Garofalo

This is exactly what my car’s breaking down had forced me to do – sit still. I looked up at the mountains behind the bank, and I thought, how fortunate that my car wouldn’t start. I may never have noticed this poem for another four years, and what a loss that would have been.

This is exactly what my car’s breaking down had forced me to do – sit still. I looked up at the mountains behind the bank, and I thought, how fortunate that my car wouldn’t start. I may never have noticed this poem for another four years, and what a loss that would have been.

Sometimes you have to be forced to stop in order to think.

I wondered who M.P. Garofalo was. If you Google M.P. Garofalo the phrase “Concrete Poetry” comes up. It seems that concrete poetry is an accepted art form. Under the link to “Concrete Poems by Michael P. Garofalo,” you find the following definition:

“Just as concrete is poured into a frame and then properly dried and cured to take some shape, concrete poems are letters and words poured into the frame of the poem to make some image-shape appear that visually amplifies the meaning and interpretations.”

It made me think of Emily Dickenson’s poems, which she refused to publish during her lifetime, because, as she emphatically wrote to her editor, they “did not print.” They needed to wait for the fluid forms of the digital page to be fully understood, since their shapes were so important to their meaning. They were a fusion of graphic art and words.

What clever person thought to actually impress Garofalo’s poem into concrete, in this completely unlikely spot! The image-shape in that setting did make one sit still – the words took on a whole new meaning, greater than the words would have just on a printed page or screen. It made me look at those mountains, looming above me, to 5000 feet, and think how when the monsoons come, the water courses down these streets, and could take with it some of the mountain’s slopes. It could move mountains, and did, long before the street and shopping malls and bank were built. And it will continue to do so long after they are gone.

And so, after pausing to look back again, I continued on my way, grateful that my car had broken down, and given me this gift on a beautiful Sunday afternoon.

Election Stress 2016, and What to Do About It

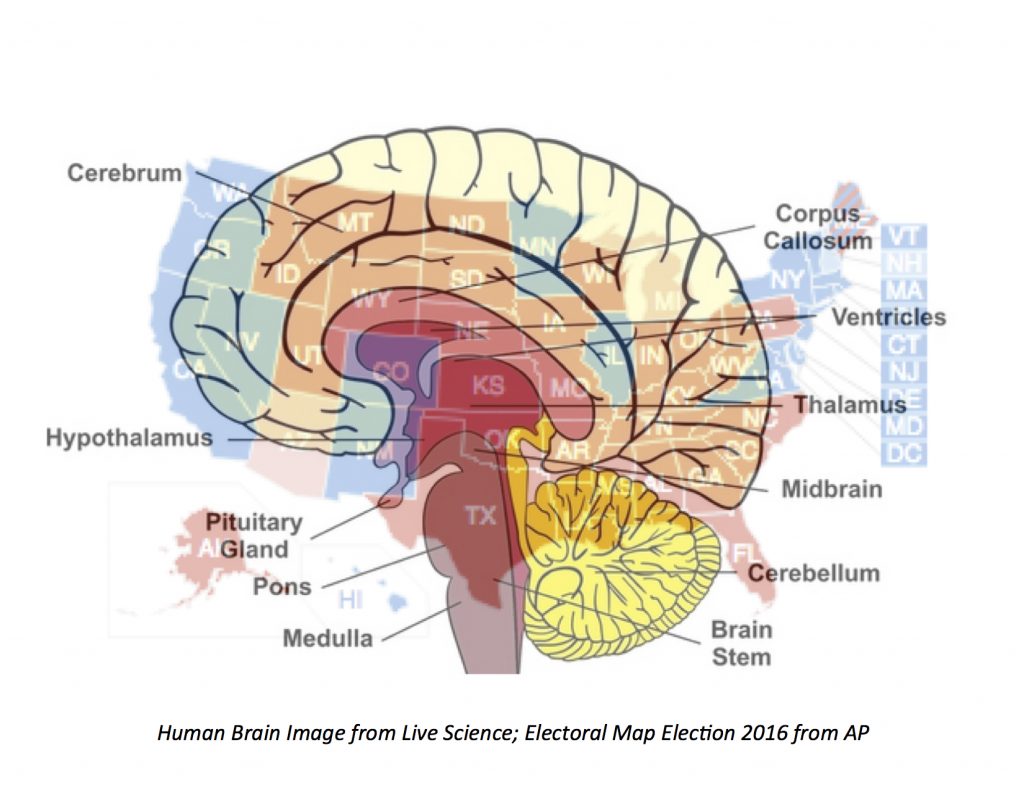

To my readers: sorry for being offline for a while – I was stressing over the elections – and apparently I am not alone. But the storm and fury of the election didn’t just cause us all to be stressed – one could argue that the brain’s stress response played a very large role in causing that storm and fury.

To my readers: sorry for being offline for a while – I was stressing over the elections – and apparently I am not alone. But the storm and fury of the election didn’t just cause us all to be stressed – one could argue that the brain’s stress response played a very large role in causing that storm and fury.In 1881, in his book called “American Nervousness, Its Causes and Consequences,” George M. Beard said: “The chief and primary cause of …[the] very rapid increase of nervousness is modern civilization, which is distinguished from the ancient by these five characteristics: steampower, the periodical press, the telegraph, the sciences, and the mental activity of women.”

Sound familiar? Just substitute the words automation, the internet, the media, and cultural change, for some of Beard’s words, and we see that nothing has changed in over a century. Had my father been alive, he would have said: “Plus ça change, plus ça rest la meme chose,” – “The more things change, the more they stay the same.”

So why is this? The brain’s stress response is a finely tuned instrument, set to trigger at the slightest change in the environment. Change and novelty are very potent stressors for all animals, even down to the lowliest fruit fly. This is a good thing, as without that stress response, when faced with a danger in a new environment, we would not have the energy to fight or flee; we would not survive. But we are living in an age of unprecedented change – change that is present, or feared in the future; change in our immediate surroundings, or distant from us; change that we cannot escape because it looms large through the internet. There is war and terrorism. There are jobs lost through automation – jobs that will never be replaced because machines and robots are doing them now. There is social change, with the influx of immigrants and clashes of cultures. There is poverty, violence and discrimination. And yes, the “mental activity of women” apparently continues to cause stress for some.

What does this have to do with the election? People said they wanted change, but what the science of stress tells us is that what they were really seeking was familiarity – with an older, simpler time. Familiarity is an effective way of reducing the stress of novelty and change. Of course we all long for a simpler time, when we imagine that none of these stressors existed, or at least that they were there in smaller amounts. So it is natural to search for a way to go back in time, to when the landscape of work and the people around were familiar. It is natural too, to place all our hopes on someone who promises to take us there. When Walt Disney designed his theme parks in the 1950s, he designed a Main Street to reflect the Main Street of his childhood. But if you look at pictures of his hometown’s Main Street, it didn’t look at all like Disneyland. There were certainly no pretty awnings and definitely no castle. It was the town he had dreamed of – a place that existed only in his imagination.

One very primal, almost reflexive way to lower the stress response is to act on it – express it, vocalize it, attack the perceived trigger, to try to get rid of it. That’s the “fight” part of the fight or flight response. This approach was unfortunately all too rampant in the lead-up to this election. But while this may feel good to the do-er in the moment, it is counter-productive in the longer term. It creates a vicious cycle that amplifies stress, especially if the perceived trigger fights back. And the stress is amplified even more if those attacks are launched relentlessly on a massive, society-wide scale, as they were throughout the election period.

But there are better ways of reducing stress – ways that don’t hurt others and ourselves, and which do ultimately get the desired result – a place of safety and comfort for all. How stressed one feels depends on the balance between the load of stress and the control we have over that stress. If you are in a high demand, high control situation, you feel stimulated – think pilot flying an airplane. In a high demand low control situation, you feel stressed – that’s the rest of us in the back of the plane when it gets bumpy. So, if the election results are making you stressed, one way to productively manage that stress is to do something to take control. Of course, you can never really be in control. But you can fool your brain into thinking that you have some control, and that will lower your stress response.

I have felt this way at a few critical times in my life when events so monumental stopped me dead in my tracks – 9/11 was one. When faced with stressful events that you can’t change, you can resolve to do whatever you can in your own sphere of expertise, to take control. If you are a teacher, teach; a builder, build; a driver, drive; a cook, cook; a healer, heal. That will give you a sense of control over the situation and doing so will lower that feeling of stress. I write and do medical research. I am already feeling less stressed just writing this, so thank you, dear readers, for helping me out!

One even better way to lower your stress response is to do those things that you do best, and do them for others. If enough of us apply our own special talents to doing good, then perhaps the cumulative good will have a chance of canceling out the bad, while lowering our collective stress in the process.

That may sound naïve, but it works. Love and compassion are actually more effective ways to counter the brain’s stress response, by activating all those positive brain hormones, nerve chemicals, and brain pathways, than is trying hard to reduce stress. When I asked the Dalai Lama whether he uses meditation to reduce stress, he shook his head. Stress, he said, was not a word in the Buddhist tradition. When I asked, why then does he meditate, he answered, compassion – love – it’s that simple.

The Dalai Lama is not the only spiritual leader who has preached this gospel. Having compassion for people on both sides – each struggling with their own stresses – change, job loss, new culture, loss of home or homeland, fear, discrimination, violence, poverty, and on and on – is one of the best ways to lower your stress response. By doing so, hopefully we will all find a new way forward, to work together to find solutions on common ground, to build instead of to tear down, and to do it together, with respect for the fears and stresses that motivate us all. That is what will make this country truly great again.

Maybe then we can all have our castles at the end of Main Street. After all, the United States was founded on these principles – that we all have certain unalienable Rights, and these include the pursuit of Happiness.