Archive for the ‘Uncategorized’ Category

COANIQUEM – Safe Niños Part 1

It started out with informal phone calls from my daughter Penny, when she and her partner Dan began working on their latest project in South America – advising COANIQUEM, a children’s burn center in Santiago, Chile. COANIQUEM’s Founder and Director, Dr. Jorge Rojas had asked Designmatters, a United Nations NGO within Pasadena’s ArtCenter College of Design, to make the spaces less scary and more inviting for their patients.Designmatters’ Director Mariana Amatulo, turned to Penny and Dan, as lead faculty for such South American Pacific Rim projects, to spearhead the initiative. After several phone calls from Penny asking my advice, we decided to formalize the relationship, and I became an official advisor, to help them turn COANIQUEM into a healing space.

The burn center serves over eight thousand child burn patients per year from across all of South America. It is a monumental task, as more than 7 million children are burned per year in Latin America, over seven times the burn rate in the developed world. More like a small village than a hospital, COANIQUEM includes a long-term care clinic, surgical outpatient services, physiotherapy, occupational therapy, a school, a chapel, and housing for the long term patients.

The Designmatters teams – usually two to three faculty and ten to twelve ArtCenter students, work closely with the NGOs and communities they are serving, to identify their greatest needs, and come up with design solutions together. It is truly social entrepreneurship working with, not just for the people who will benefit. The COANIQUEM project was named “Safe Niños” – to continue the theme that their first project, “Safe Agua” had begun.

I gave my first lecture to the ArtCenter student group shortly after they had returned to LA from their first trip to Chile. They had lived on site at COANIQUEM for two weeks, staying in the same dormitories as the families and patients. They had spent their days talking with and observing the day-to-day activities of all the staff, the patients, and their families, to identify their greatest needs and wishes for improvements.

At that point the students had barely formed their small group teams, and some had only a vague idea of their plans of action. So our interaction was mostly didactic – I gave my PowerPoint presentation on “Healing Spaces,” outlining elements of place that can stress or calm. When I came to the slide of me in Disneyland, on my 2008 behind-the-scenes-tour when I was researching my book Healing Spaces, the students nearly leaped out of their seats and begged me to please, please get them a behind-the-scenes tour of Disneyland too! At first I laughed at the idea, but then figured it was worth a try.

The design issues at COANIQUEM were much the same as those with which Disney’s Imagineers dealt when designing the theme park: how to move people through a space without being there to guide them every step of the way, and at the same time bringing them from fear and anxiety to hope and happiness. COANIQUEM had an entrance, long hallways, and many buildings that needed to be made easier to navigate and less threatening to the kids.

As soon as I returned to Tucson, I e-mailed Bruce Vaughn who, as VP of Disney Imagineering had given me the tour in 2008. He had since risen to Chief Creative Officer of Disney Imagineering, and enthusiastically arranged the tour for the group. He, and all the Imagineers we met were happy to apply their skills and talents to training the next generation to do good in the world through design.

It was wonderful to watch the students drink in every word, some taking notes, many taking pictures, and all seeing the Park through the eyes of burgeoning young design professionals.

To be continued….

The “Green Road”: Healing wounds of war with nature, Part 1

After the young service woman in full Navy camo cleared me for base access at the Visitor’s Entrance check-point, she pointed to the familiar white art deco tower of what used to be called the Bethesda Navy Hospital.“Just head up there, turn left and head straight to the USO. It’s a long walk,” she cautioned.

As I started my trek up the hill I felt anxious, not knowing exactly where I was going. But as soon as I saw a small printed sign by the edge of the road festooned with a green ribbon, I smiled. Finding my way to the site would be like a scavenger hunt!

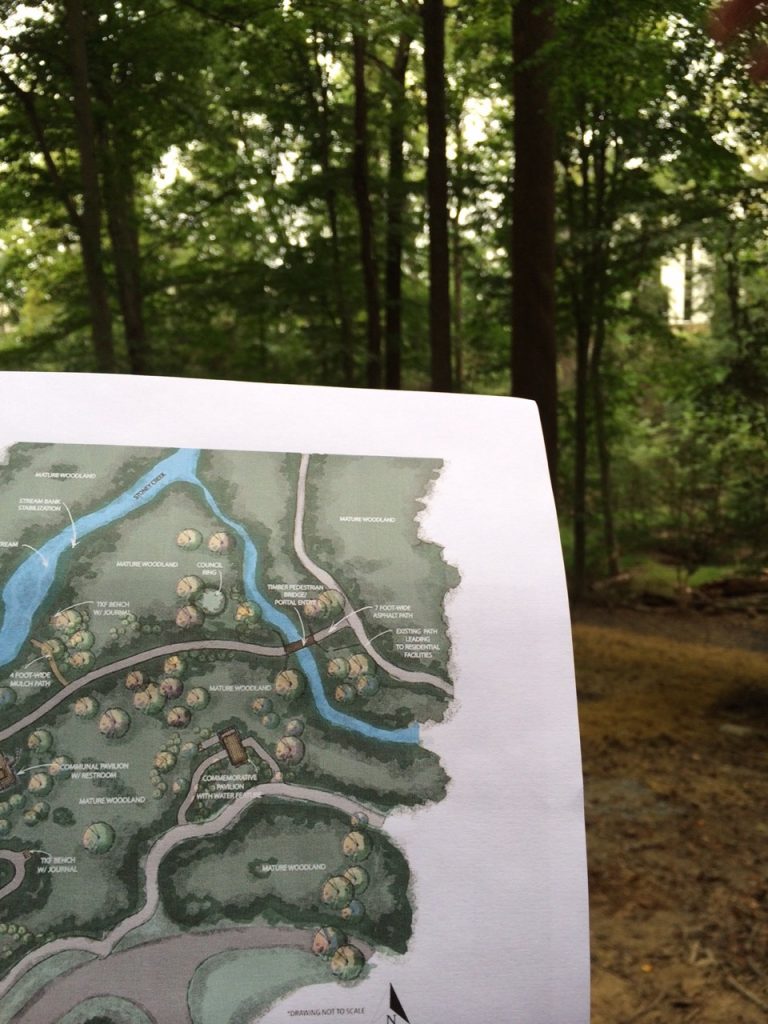

I was at the Walter Reed National Military Medical Center military base in Bethesda, Maryland, for the opening of the “Green Road” Project. It had been 5 years in the making. The goals: to retrofit a branch of the Rock Creek that flows through the base, make it ADA accessible for wheelchairs and anyone with difficulty walking, and create a healing forest glen where wounded warriors and their families could gather and find respite while being treated at the many hospitals on base.

I had been involved in the project from the start, having advised the CEO and founder of the TKF Foundation and his Board on the most impactful way to dispose of the Foundation’s funds as they searched for a way to sunset it. Up until that time the Foundation had built hundreds of healing, sacred nature spaces throughout Maryland and the mid-Atlantic region. They wanted to use their remaining funds to build a smaller number of gardens that would have greater national impact. They had asked me, and a group of experts, to advise them on how to accomplish that.

I had been working with Capt. Fred Foote, a retired Navy doc, at the then Bethesda Naval Hospital. As he worked to bring holistic mind-body integrative treatments into the armamentarium of military medical care, he dreamed of creating a healing forest glen as a sanctuary for service personnel and their families. It was a no-brainer, I thought – put him together with TKF to do it. Building this nature sanctuary at the nation’s flagship medical center – the one where Presidents are treated – would be sure to have tremendous national impact.

As I picked my way along the base’s busy urban street, past the hospital’s main entrance, a continuous stream of trucks and cars passed by, leaving behind their smells of exhaust and diesel. Loud machinery noises filled the air – constant humming emanating from whole buildings filled with heating and air conditioning equipment for the base; jack-hammering and clangs of construction equipment. The sidewalk was sloped and there were many streets to cross. I couldn’t imagine how anyone in a wheel chair or on crutches could navigate this route without stress, twice daily to and from their living quarters to the hospital.

To be continued…

Lasting Art, Part 2: Crossing the Finish Line

Shortly before Susan Sebastian died of a life-long illness, she had told her mother, Elise Braun, that she wanted original art placed in every room in every hospital in Vermont, so tired was she of looking at the bare walls. At the suggestion of Elise’s cousin, Alex Ryley, a New York City elder law attorney who had read Healing Spaces, she and Foundation Manager Gil Myers, used the book as an inspiration and guide for selecting art throughout the seven years of the project.

Elise Braun was too ill to attend the Art Center event. When I spoke (click HERE to watch the video), I thought she was listening via Skype, but it turned out the Skype connection failed. She had to wait until the day after the event to hear about it in person through Gil Myers and her friend, Deb Clark, a nurse. Both shared how happy Elise was to know that her work was complete. In Clarke’s words,

It was a treasured time (as Elise) listened, looked at photos, and asked questions with a smile from ear to ear.Braun said:

This final installation was the most celebrated. Bennington Hospital really outdid themselves. How great (it was that) people heard about Dr. Sternberg’s work that inspired Gil and me.Braun died peacefully just a few days later. Like a marathon runner, she had pushed herself through to the project’s finish.

When I heard of Elise Braun’s passing, I was reminded of one of my first patients when I was a young medical student. My patient who was near the end, seemed well enough when I bid her good-bye for the weekend, and told her that I would see her on Monday. She smiled quietly and said she was looking forward to seeing her son that weekend, and thought that this would be her final good-bye to me. When I returned on Monday, her bed was empty and the nurses told me that she had died quietly and at peace shortly after her son had visited. This was my first experience with a patient waiting to die until a loved one visited or a special event in their lives was accomplished – a wedding, a birth, a graduation.

Many healthcare professionals have had such experiences. I have had them in my own family. When my mother was dying of cancer, she waited for my aunt, who with my uncle were driving back to Montreal as fast as they could from their winter home in Florida. My mother had slipped into unconsciousness before they arrived and we all thought they would get there too late. But when my aunt – my mother’s sister, entered the hospital room, my mother raised herself up on the bed with all her strength and called out my aunt’s name. Then she slipped back into unconsciousness and died a few days later.

I couldn’t help but feel that Elise Braun waited for her life’s mission to be complete before allowing herself to slip away. Gil Myers and Deb Clark both thought that it was so. I would like to think that my words and my book played a small part in helping her to achieve that mission, which gave her a sense of peace and calm and fulfillment that her job was done.

That would be the greatest satisfaction any author could hope for.