Archive for the ‘Healing Spaces’ Category

Office of the Future?

Judging by the media attention, our recent British Medical Journal: Occupational Environmental Medicine study (Casey Lindberg et al. & GSA’s “Wellbuilt for Wellbeing” Team, 2018) clearly struck a chord. It seems that workers – at least those who commented online, viscerally hate their open office settings. But what we found, using objective measures collected from wearable devices, was that office workers in open office settings were 32% more active than those in private offices, 20% more active than those in cubicles, and the more active workers were less stressed during after work hours. Such differences, especially when cumulative over a working lifetime, are well within the medically relevant range. A 2018 report summarizing ten studies’ research findings of more than 17,000 people (American Journal of Preventive Medicine) found that simply replacing 30 minutes of sedentary activity daily with 30 minutes of even mild activity significantly reduced BMI (Body Mass Index = weight/height), risk of diabetes, cardiovascular disease and all-cause mortality. Imagine – your office could be part of your daily exercise regime – without any effort at all on your part. And yet people complain of noise, distraction, feeling watched. Indeed, other studies using different measures have reported negative effects (Philosophical Transacations of the Royal Society B). The open offices we studied were designed purposefully to give workers many choices for different kinds of work activities, including quiet areas for individuals, private conversations or small meetings. Although, without more research, we won’t know the reasons, it may be that people in the open offices moved more in order to get to those different spaces. We are entering a new era, where fewer people need to go to an office to work. More are telecommuting, working from home, or wherever they happen to be – coffee shops, the beach. Indeed, at an upcoming summit “RETHINK: Office of the Future: New York“, where I will be speaking, building owners and industry leaders will be grappling with how to design offices to adapt and stay ahead of the times. So, employers, if you want to keep your workers healthy, work with experts to get the objective measures you need to design your offices thoughtfully. In the meantime, workers, you can think of your office as your new gym!

Judging by the media attention, our recent British Medical Journal: Occupational Environmental Medicine study (Casey Lindberg et al. & GSA’s “Wellbuilt for Wellbeing” Team, 2018) clearly struck a chord. It seems that workers – at least those who commented online, viscerally hate their open office settings. But what we found, using objective measures collected from wearable devices, was that office workers in open office settings were 32% more active than those in private offices, 20% more active than those in cubicles, and the more active workers were less stressed during after work hours. Such differences, especially when cumulative over a working lifetime, are well within the medically relevant range. A 2018 report summarizing ten studies’ research findings of more than 17,000 people (American Journal of Preventive Medicine) found that simply replacing 30 minutes of sedentary activity daily with 30 minutes of even mild activity significantly reduced BMI (Body Mass Index = weight/height), risk of diabetes, cardiovascular disease and all-cause mortality. Imagine – your office could be part of your daily exercise regime – without any effort at all on your part. And yet people complain of noise, distraction, feeling watched. Indeed, other studies using different measures have reported negative effects (Philosophical Transacations of the Royal Society B). The open offices we studied were designed purposefully to give workers many choices for different kinds of work activities, including quiet areas for individuals, private conversations or small meetings. Although, without more research, we won’t know the reasons, it may be that people in the open offices moved more in order to get to those different spaces. We are entering a new era, where fewer people need to go to an office to work. More are telecommuting, working from home, or wherever they happen to be – coffee shops, the beach. Indeed, at an upcoming summit “RETHINK: Office of the Future: New York“, where I will be speaking, building owners and industry leaders will be grappling with how to design offices to adapt and stay ahead of the times. So, employers, if you want to keep your workers healthy, work with experts to get the objective measures you need to design your offices thoughtfully. In the meantime, workers, you can think of your office as your new gym!COANIQUEM – Safe Niños Part 2

On my third meeting with the students, a small core of three teams remained, each continuing the project through a second term. Each team presented their projects that had matured and were ready to take back to Chile to install. The first student, Alvin, presented the story and animal characters his team had created to help guide the children through the magic land through which they would be “flying” as they went on their healing journey.  The land, complete with a colorful map that resembled a cross between Middle Earth and Candy Land, was, like Chile – long and narrow, flanked with whimsical mountains peopled by the trees and animals of Chile.

The land, complete with a colorful map that resembled a cross between Middle Earth and Candy Land, was, like Chile – long and narrow, flanked with whimsical mountains peopled by the trees and animals of Chile.  The waiting room was to be the entrance to this magical kingdom, and the doors leading to treatment rooms along the long hallways were to be decorated with charming animal characters inviting the young patients in. There was even a passport that the children and their families would receive when they arrived in the waiting room, to be stamped in every treatment room when they received their compression garments, physio- or occupational therapy.

The waiting room was to be the entrance to this magical kingdom, and the doors leading to treatment rooms along the long hallways were to be decorated with charming animal characters inviting the young patients in. There was even a passport that the children and their families would receive when they arrived in the waiting room, to be stamped in every treatment room when they received their compression garments, physio- or occupational therapy.

Then students Behnia and Anna presented their solution to motivate the teens, who had been returning to the clinic for years for multiple treatments: a “Teen Zone” flanked by mural-painted shipping containers that were already being used for storage on the site. The area would be covered with colorful sail shades and was made attractive to teens with a dance area and hammocks.

Finally, Nicholas and Dave presented their low and hi tech brightly colored “toys,” designed to help the children participate in physio- and occupational therapy treatments to increase mobility and activity, and reduce stress. The design challenge that they were solving was how to provide the therapists measureable feedback on the progress of treatment, while motiving the kids with musical and visual feedback.

It was a remarkable display, accomplished over a few short months. The passion of the students shone through. An added benefit: the project had inspired the staff, the patients, and their families with pride for COANIQUEM and its cutting edge treatments, giving them happiness and hope for healing, even before the projects were installed. Then, to top it off, one of the students – Alvin, won a grant to complete his project and fly back to Chile to install it, launching his career while doing good in the world. What better outcome could there be!

COANIQUEM – Safe Niños Part 1

It started out with informal phone calls from my daughter Penny, when she and her partner Dan began working on their latest project in South America – advising COANIQUEM, a children’s burn center in Santiago, Chile. COANIQUEM’s Founder and Director, Dr. Jorge Rojas had asked Designmatters, a United Nations NGO within Pasadena’s ArtCenter College of Design, to make the spaces less scary and more inviting for their patients.Designmatters’ Director Mariana Amatulo, turned to Penny and Dan, as lead faculty for such South American Pacific Rim projects, to spearhead the initiative. After several phone calls from Penny asking my advice, we decided to formalize the relationship, and I became an official advisor, to help them turn COANIQUEM into a healing space.

The burn center serves over eight thousand child burn patients per year from across all of South America. It is a monumental task, as more than 7 million children are burned per year in Latin America, over seven times the burn rate in the developed world. More like a small village than a hospital, COANIQUEM includes a long-term care clinic, surgical outpatient services, physiotherapy, occupational therapy, a school, a chapel, and housing for the long term patients.

The Designmatters teams – usually two to three faculty and ten to twelve ArtCenter students, work closely with the NGOs and communities they are serving, to identify their greatest needs, and come up with design solutions together. It is truly social entrepreneurship working with, not just for the people who will benefit. The COANIQUEM project was named “Safe Niños” – to continue the theme that their first project, “Safe Agua” had begun.

I gave my first lecture to the ArtCenter student group shortly after they had returned to LA from their first trip to Chile. They had lived on site at COANIQUEM for two weeks, staying in the same dormitories as the families and patients. They had spent their days talking with and observing the day-to-day activities of all the staff, the patients, and their families, to identify their greatest needs and wishes for improvements.

At that point the students had barely formed their small group teams, and some had only a vague idea of their plans of action. So our interaction was mostly didactic – I gave my PowerPoint presentation on “Healing Spaces,” outlining elements of place that can stress or calm. When I came to the slide of me in Disneyland, on my 2008 behind-the-scenes-tour when I was researching my book Healing Spaces, the students nearly leaped out of their seats and begged me to please, please get them a behind-the-scenes tour of Disneyland too! At first I laughed at the idea, but then figured it was worth a try.

The design issues at COANIQUEM were much the same as those with which Disney’s Imagineers dealt when designing the theme park: how to move people through a space without being there to guide them every step of the way, and at the same time bringing them from fear and anxiety to hope and happiness. COANIQUEM had an entrance, long hallways, and many buildings that needed to be made easier to navigate and less threatening to the kids.

As soon as I returned to Tucson, I e-mailed Bruce Vaughn who, as VP of Disney Imagineering had given me the tour in 2008. He had since risen to Chief Creative Officer of Disney Imagineering, and enthusiastically arranged the tour for the group. He, and all the Imagineers we met were happy to apply their skills and talents to training the next generation to do good in the world through design.

It was wonderful to watch the students drink in every word, some taking notes, many taking pictures, and all seeing the Park through the eyes of burgeoning young design professionals.

To be continued….

The “Green Road”: Healing wounds of war with nature. Part 2

The first sign that I was getting close to the “Green Road” was a view of a grove of trees and a flock of geese staidly crossing the street nearby. The urban noises began to fade as sounds of crickets and birds gradually replaced them. It was like the “slow fades” between lands in a Disney theme park. Soon, I was surrounded by trees as I entered an entirely new world.  The gently sloping paved switchback path led to an old iron bridge across the Rock Creek. As I crossed the bridge over the pebbled lazy stream below, I could see deer grazing among the trees. The leaf-strewn path led to an open area where large granite rocks had been placed in a circle – inviting visitors to gather and share songs and stories. Farther on, beside the stream, was one of the signature large oak benches that the TKF Foundation places in all their gardens. There, visitors can contemplate in peace, or write their thoughts in a waterproof journal placed underneath the seat. Up on the steep hillside above the stream was a simple covered wooden structure, held by a low dry rock wall. A single large slatted wooden bench at its back, welcomed one to sit in quiet and remember loved ones lost in battle.

The gently sloping paved switchback path led to an old iron bridge across the Rock Creek. As I crossed the bridge over the pebbled lazy stream below, I could see deer grazing among the trees. The leaf-strewn path led to an open area where large granite rocks had been placed in a circle – inviting visitors to gather and share songs and stories. Farther on, beside the stream, was one of the signature large oak benches that the TKF Foundation places in all their gardens. There, visitors can contemplate in peace, or write their thoughts in a waterproof journal placed underneath the seat. Up on the steep hillside above the stream was a simple covered wooden structure, held by a low dry rock wall. A single large slatted wooden bench at its back, welcomed one to sit in quiet and remember loved ones lost in battle.

The path led to a tiny wooden cabin whose roof shaded a wooden picnic bench with iron joints salvaged from the World War II battleship SS Diamond Head. A crowd of civilians and military personnel from the Army, Navy and Marines were gathered there, listening as the sweet voices of two women singing America the Beautiful filled the clearing. Photographers and TV camera crews stood behind the rows of people on folding chairs. After speeches and thank you’s from dignitaries, including Capt. Fred Foote, the Base Commander, Senator Barbara Mikulski, and the funding partners –The Institute on Integrative Health, and TKF’s Tom Stoner, the ribbon cutting officially opened the site (a green ribbon, of course!). We were then free to wander in the grove before retiring to the USO lounge for a barbeque lunch.

The path led to a tiny wooden cabin whose roof shaded a wooden picnic bench with iron joints salvaged from the World War II battleship SS Diamond Head. A crowd of civilians and military personnel from the Army, Navy and Marines were gathered there, listening as the sweet voices of two women singing America the Beautiful filled the clearing. Photographers and TV camera crews stood behind the rows of people on folding chairs. After speeches and thank you’s from dignitaries, including Capt. Fred Foote, the Base Commander, Senator Barbara Mikulski, and the funding partners –The Institute on Integrative Health, and TKF’s Tom Stoner, the ribbon cutting officially opened the site (a green ribbon, of course!). We were then free to wander in the grove before retiring to the USO lounge for a barbeque lunch.

I had wandered the grove myself on the Saturday before the event, picking pebbles by the stream, sitting on the benches listening to the forest sounds: the water swooshing over rocks, the wind in the trees, the birds’ cheeping, and the crunch of leaves underneath my feet.

It was indeed a healing place – a place of peace amidst the clatter and fray of the outside world; a place to heal the wounds of war.

The “Green Road”: Healing wounds of war with nature, Part 1

After the young service woman in full Navy camo cleared me for base access at the Visitor’s Entrance check-point, she pointed to the familiar white art deco tower of what used to be called the Bethesda Navy Hospital.“Just head up there, turn left and head straight to the USO. It’s a long walk,” she cautioned.

As I started my trek up the hill I felt anxious, not knowing exactly where I was going. But as soon as I saw a small printed sign by the edge of the road festooned with a green ribbon, I smiled. Finding my way to the site would be like a scavenger hunt!

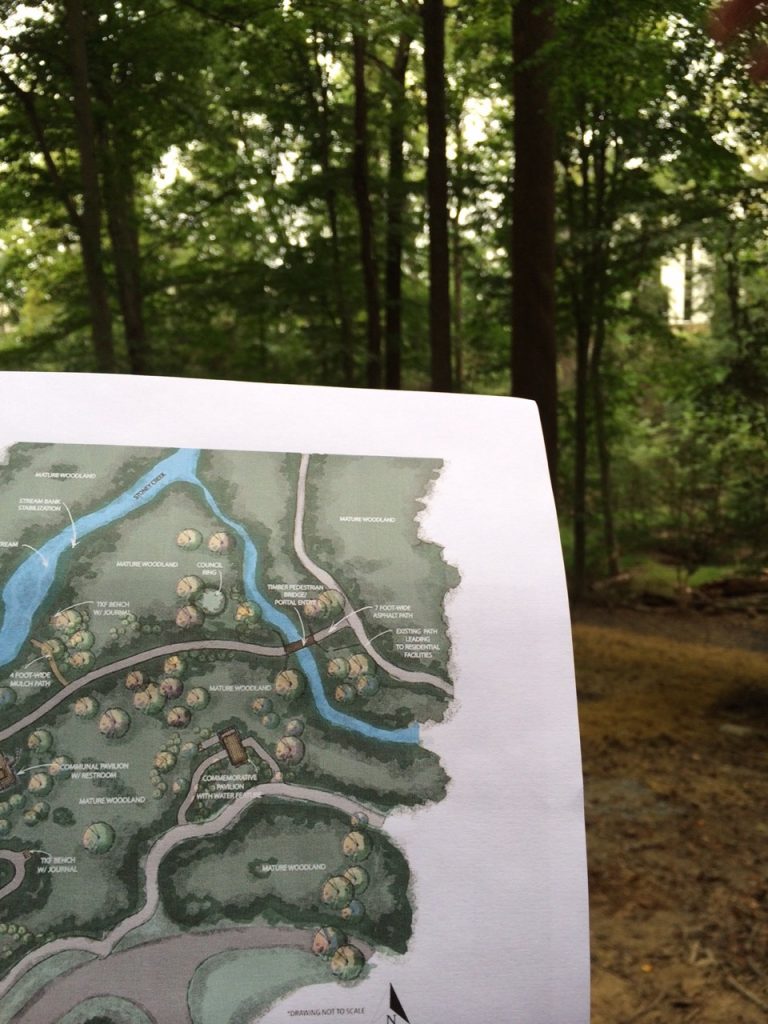

I was at the Walter Reed National Military Medical Center military base in Bethesda, Maryland, for the opening of the “Green Road” Project. It had been 5 years in the making. The goals: to retrofit a branch of the Rock Creek that flows through the base, make it ADA accessible for wheelchairs and anyone with difficulty walking, and create a healing forest glen where wounded warriors and their families could gather and find respite while being treated at the many hospitals on base.

I had been involved in the project from the start, having advised the CEO and founder of the TKF Foundation and his Board on the most impactful way to dispose of the Foundation’s funds as they searched for a way to sunset it. Up until that time the Foundation had built hundreds of healing, sacred nature spaces throughout Maryland and the mid-Atlantic region. They wanted to use their remaining funds to build a smaller number of gardens that would have greater national impact. They had asked me, and a group of experts, to advise them on how to accomplish that.

I had been working with Capt. Fred Foote, a retired Navy doc, at the then Bethesda Naval Hospital. As he worked to bring holistic mind-body integrative treatments into the armamentarium of military medical care, he dreamed of creating a healing forest glen as a sanctuary for service personnel and their families. It was a no-brainer, I thought – put him together with TKF to do it. Building this nature sanctuary at the nation’s flagship medical center – the one where Presidents are treated – would be sure to have tremendous national impact.

As I picked my way along the base’s busy urban street, past the hospital’s main entrance, a continuous stream of trucks and cars passed by, leaving behind their smells of exhaust and diesel. Loud machinery noises filled the air – constant humming emanating from whole buildings filled with heating and air conditioning equipment for the base; jack-hammering and clangs of construction equipment. The sidewalk was sloped and there were many streets to cross. I couldn’t imagine how anyone in a wheel chair or on crutches could navigate this route without stress, twice daily to and from their living quarters to the hospital.

To be continued…

Ice Cream

I know I shouldn’t admit this, but I love ice cream. Not exactly your top health food, but at least it does contain calcium. I rarely eat it at home, and reward myself when I travel, with a scoop of the local specialties. In Italy, there is gelato; in France crème glacée – each with very different textures and flavors than American ice cream.  I first tasted green tea ice cream at a street vendor’s cart in Shizuoka, Japan, and have since had it at pretty much any sushi restaurant that serves it. I always thought that “mochi” ice cream – a sweet confection of ice cream wrapped in pounded sticky rice, was also a Japanese specialty, but it turns out it was invented by a Japanese American, Frances Hashimoto, right in L.A.’s Little Tokyo, where I first tasted it – of course, filled with green tea ice cream.

I first tasted green tea ice cream at a street vendor’s cart in Shizuoka, Japan, and have since had it at pretty much any sushi restaurant that serves it. I always thought that “mochi” ice cream – a sweet confection of ice cream wrapped in pounded sticky rice, was also a Japanese specialty, but it turns out it was invented by a Japanese American, Frances Hashimoto, right in L.A.’s Little Tokyo, where I first tasted it – of course, filled with green tea ice cream.

As a child, my favorite flavors were vanilla, orange, and banana. It was a thrill to hand over our coins in exchange for a sugar cone, when my sister and best friend and I were first allowed to walk, alone, the five blocks to our local ice cream parlor in Montreal. On a recent trip back, I visited the place. Its name is changed and, like the whole area, it is much gentrified, with sidewalk tables and flavors like “Lavande et Miel” (Lavender and Honey) – divine, but not my simpler childhood memories.

In Burlington, Vermont they call soft ice cream “cremees,” and it is impossible to be in that state without tasting maple cremees in each locale, and comparing them – the equivalent of a pub crawl for beer, but in this case an ‘ice cream crawl.’

And then there is Ben and Jerry’s. Shockingly there is no plaque commemorating the site of a former gas station in downtown Burlington, where the boys first started scooping their product. It is just an empty lot. However, on Church Street, Burlington’s walking promenade, a second street sign sits atop the one for Cherry Street, on the corner of which the Ben and Jerry’s shop is situated. It reads “Cherry Garcia.”

This year, when we visited the Ben and Jerry’s Factory in Waterbury, Vermont, on a July weekend, the place was crowded with families with young children, teenagers, and older adults of many nationalities all waiting for their tours. In summer these are spaced every ten minutes, from 9am through to 9pm closing. I could hear many languages besides American, Brit, and Australian English, including French, Chinese, and German. This and the world map in the entrance lobby showing all the locations where Ben and Jerry’s ice cream is sold, fit with my having had a cup of the stuff at Australia’s Sydney Opera House, and seeing it in a vending machine at Heathrow Airport in London.

What is it about ice cream that speaks to so many people around the world, young and old and everything in between?

I posed this question to Jerry Greenfield when we met at a wedding last year in Burlington, Vermont. The bride’s mother was a long-time friend of Jerry’s and Ben Cohen, and had helped them out at the shop almost from its inception, even naming and perfecting some flavors. Jerry’s wedding gift to the young couple: he and his son were on hand to scoop the ice cream he had provided for the guests. The bride and groom were from Vienna, and their many Austrian friends were thrilled at the chance to take selfies while being handed scoops from Jerry himself. And truth be told, so was I.

I shared with him my personal ritual when I lived in Washington, DC, of eating a chocolate-coated Cherry Garcia while walking under the arching cherry trees in full bloom. It was often cold at that time of year, but the experience always boosted my spirits.

We talked about how smell and taste are the most ancient and direct routes to the brain’s emotional and memory centers, triggering release of pleasure chemicals in the brain’s reward centers. Jerry’s wife, a psychologist, and I continued the conversation after he and his son had to leave to tend to the ice cream for the wedding reception. It seems there is a rather narrow temperature window between frozen too hard and soupy melted, when the flavor and texture of ice cream is just right. The science of ice cream creation clearly involves both chemistry and sensory neuroscience.

Chelsea Flower Show Part 3: My Favorite Gardens

The Chelsea garden themes were as varied as the riots of color and different plants displayed: historic gardens, commemorative gardens (for the Queen’s 90th birthday), squares of different plants of matching colors, and squares of similar plants of different colors – roses, orchids, tulips – it went on and on. Then there were wilder plantings, like woodland meadows. Some were unique – an old mill next to a stream with a bucket of colored wool spilling out, surrounded by plants for dyeing.

The Chelsea garden themes were as varied as the riots of color and different plants displayed: historic gardens, commemorative gardens (for the Queen’s 90th birthday), squares of different plants of matching colors, and squares of similar plants of different colors – roses, orchids, tulips – it went on and on. Then there were wilder plantings, like woodland meadows. Some were unique – an old mill next to a stream with a bucket of colored wool spilling out, surrounded by plants for dyeing.My favorites were the St. John’s Hospice Garden – “A Modern Apothecary,” and the LG “Smart Garden” – both filled with flowering plants of pink and purple pastel hues. I was not alone – both gardens had won Silver-Gilt Medals from the Royal Horticultural Society. Both were meant as tranquil places, and each also had a second theme – the Smart Garden merged modern technology with the natural environment, and every element in the Modern Apothecary garden had been shown to have some beneficial effect on healing.

As its name suggests, the Apothecary Garden contained herbs and plants used for their medicinal properties – fragrant purple-flowered rosemary, lavender, and thyme; daisy-like flowers of feverfew, white flowering hawthorne, golden marigold, and delicate blue flowered flax.

The layout too, and architectural elements also had healing aspects. A pale pink climbing rose trellis arch marked the entrance to the garden. In an alcove adorning the back of the garden stood a bronze statue of a snake winding around the staff of Aesclepius – the universal symbol of healing and medicine.  Connecting the two was a brick paved path lined with a few oak benches.

Connecting the two was a brick paved path lined with a few oak benches.

This garden’s layout – an entrance arch, a focal point (the statue), a path, a place to sit, is one that is used in all the sacred, healing gardens created by the TKF Foundation: an Annapolis, Maryland-based non-profit dedicated to creating healing, sacred gardens throughout the US. The arch defines the space, and helps keep it sacred. The focal point draws you towards it and guides your meanderings along the paths, in quiet meditation.

The places to sit also provide an opportunity for quiet contemplation. The TKF Foundation’s signature benches, placed in all their sacred spaces, are large semi-circular oak, made from oak barrels that Founder and CEO Tom Stoner had purchased from a defunct brewery. He simply cut the large barrels in half and re-assembled them to make the benches. Under each bench is placed a waterproof notebook where visitors can record their thoughts. The “Green Road” healing forest glen at the Walter Reed National Medical Center in Bethesda, Maryland, currently under construction in partnership with the TKF Foundation, will have these features too.

I have always found gardens to be my sanctuary, my places of peace – places I escape to when I am stressed or distressed. Some of my favorites, which I describe in Healing Spaces, are the Bishop’s Garden at the National Cathedral in Washington, DC; the Huntington Gardens in LA; and a lovely mature Japanese garden on the roof of a hotel in downtown LA’s ‘Little Tokyo.’ You would never guess that the tall trees that shade an azalea-lined stream and the high waterfall splashing into a pebble beach, all sit atop the third floor of a convention space attached to the hotel. All these gardens have the same features, on different scales – an entrance-way, a winding path, and benches on which to sit, and many have water elements.

Perhaps my love of gardens comes from my mother – although I didn’t inherit her love of gardening. I would rather enjoy the fruits of someone else’s labors. My mother tended our garden in Montreal with love and dedication, rejoicing in the young shoots that pushed up through the dry leaves and melting snow in early spring, welcoming the spring and summer rains that fed those plants, and carefully protecting them in the fall before the winter’s cold and storms.

Now that the Chelsea Flower Show is over, the St. John’s Modern Apothecary Garden will be moved to its permanent home at St. John’s Hospice, a palliative care hospital in St. John’s Wood, London. There, patients will be able to find respite, even at the end of life, and their families and loved ones will find a place of peace with them.

Water

During a recent interview, Tucson radio show host, Rabbi Cohon asked me what it is about water that is so healing (listen to PART 1, PART 2). Water seemed to him to be a common feature of many of the more than one hundred and forty sacred healing sites around the world, which he had visited the previous year.There is no question that water – seeing it, smelling it, hearing it, being in it, can calm and help heal. Perhaps ancient peoples recognized the hygienic effects of water. Swimming and bathing in warm waters helps aching joints, and the exercise is of course healthy.

As I sit on a boat on Lake Champlain in Northern Vermont, I can smell the earthy fragrance of the lake and hear the lapping of the gentle waves upon the hull. Why did this give me a sense of calm?

As I sit on a boat on Lake Champlain in Northern Vermont, I can smell the earthy fragrance of the lake and hear the lapping of the gentle waves upon the hull. Why did this give me a sense of calm?

Perhaps it was because it reminded me of many summers visiting my sister and brother-in-law at their “camp” on Methuen Pond outside of Boston. That brought my thoughts to those times as a medical student when I would take a tiny Sunfish sailboat out on the Charles River that separates Boston from Cambridge, Massachusetts. Digging deeper into my memory, I remembered the summers when my sister and I used to visit our best friend’s family cottage at Lac Nominingue – one hundred and twenty-five miles north of Montreal, or when we would visit my aunt and uncle and cousins at their rented cottage on Trout Lake, only sixty miles north of Montreal.

I remembered swimming in the bracing water and running back to the house shivering, in Nominingue to stand in front of the warm fireplace; at Trout Lake to have a lunch of macaroni and cheese, which my aunt had at the ready for us teeth-chattering children. With our parents we sometimes would drive south from Montreal to Vermont, New Hampshire, or Upstate New York, and stay in little pine paneled cottages next to running brooks, where we would step from stone to stone. So, water for me was all these memories rolled into one – memories of vacation, family, friends, and love.

Now, since moving to Tucson, Arizona in 2012, I spend summers with my partner, telecommuting from Vermont. On weekends, from our boat on Lake Champlain, I look out over the ever-changing water towards the hills and mountains – Vermont’s Green Mountains, and New York’s Adirondacks. It is a meditation.

Now, since moving to Tucson, Arizona in 2012, I spend summers with my partner, telecommuting from Vermont. On weekends, from our boat on Lake Champlain, I look out over the ever-changing water towards the hills and mountains – Vermont’s Green Mountains, and New York’s Adirondacks. It is a meditation.

When floating on six trillion gallons of water – Lake Champlain is the “sixth Great Lake” – it is hard to imagine that there are places on earth where there is none. In Tucson, I have become acutely aware of lack of water, and carefully monitor my use of it. We rejoice when the Rillito River, most of the year a dry riverbed, occasionally fills with water after a storm. People line up to photograph the roiling waters charging past.

When floating on six trillion gallons of water – Lake Champlain is the “sixth Great Lake” – it is hard to imagine that there are places on earth where there is none. In Tucson, I have become acutely aware of lack of water, and carefully monitor my use of it. We rejoice when the Rillito River, most of the year a dry riverbed, occasionally fills with water after a storm. People line up to photograph the roiling waters charging past.

When the monsoon rains come to Tucson in summer, or the quieter steady rains in early spring, the desert bursts into bloom – subtle by Vermont standards, but dramatic against the backdrop of rocks and scrub. When it rains all day or all night in Vermont, I appreciate all the more the greenery that follows and the profusion of wildflowers in the roadside and fields.

While the desert holds many charms, how awful it would be without water all the time. The contrast makes me all the more conscious of how important it is to preserve this most precious of all our commodities.

Lasting Art, Part 3: The Work Continues

A few days after I returned to Burlington, Vermont from the Susan Sebastian event at the Southern Vermont Art Center (Part 1, Part 2), I sat down for coffee with Gil Myers, a retired attorney who had set up and now manages the Foundation. He had been a longtime friend of Susan Sebastian’s mother, Elise Braun. He had suggested we meet at a coffee house across from the Court House in downtown Burlington. A small man with white hair and twinkly eyes, he carried a gnarled wooden country walking stick, much like Gandalf or Sam Gamgee might have done in Lord of the Rings.  Self effacing and humble, he downplays his central role in carrying through Susan Sebastian’s dying wish, to install original art in every patient room in every hospital in Vermont. At first Elise Braun was the moving force, he recounted, but after they had completed placing art in three hospitals, Elise fell ill and Myers was the one who carried the project through to its completion. Nonetheless, he insisted throughout that it was not his but Elise’s achievement – he was simply the instrument who completed the task. As he told me – “that’s what lawyers do.”

Self effacing and humble, he downplays his central role in carrying through Susan Sebastian’s dying wish, to install original art in every patient room in every hospital in Vermont. At first Elise Braun was the moving force, he recounted, but after they had completed placing art in three hospitals, Elise fell ill and Myers was the one who carried the project through to its completion. Nonetheless, he insisted throughout that it was not his but Elise’s achievement – he was simply the instrument who completed the task. As he told me – “that’s what lawyers do.”

Myers shared with me more of Elise Braun’s character and spirit. “She was such a vital person,” he recalled, “she radiated vitality and energy.” At one time Elise, her husband, and her daughter Susan had lived in Stowe, Vermont. They used to attend an Episcopal Church about two miles up the Mountain road from the Village, near the Stowe Ski area.

The day I went to visit, the mist alternated with rain, and the little garden bloomed bright. Elise had noticed that many of the older congregants had difficulty getting to church. So she went to school and trained to become an Episcopal Deacon, in order to minister to those unable to attend. As much as book-learning and helping others, she loved outdoor sports – she and her husband used to figure skate in winter and hike in summer.

The day I went to visit, the mist alternated with rain, and the little garden bloomed bright. Elise had noticed that many of the older congregants had difficulty getting to church. So she went to school and trained to become an Episcopal Deacon, in order to minister to those unable to attend. As much as book-learning and helping others, she loved outdoor sports – she and her husband used to figure skate in winter and hike in summer.

Myers too was a sportsman – a fly fisherman. I asked if he had stopped by the Orvis store and headquarters in Manchester, Vermont, just a short drive from the Southern Vermont Art Center where the Susan Sebastian event had been held. He smiled and launched into a wonderful story about a friend who had taught one of the Rockefeller women fly-fishing. In thanks, she sent the friend a silver-handled hand-made bamboo Orvis fly-fishing rod, engraved with his name and thanks for having taught her the sport. Now that’s a great fishing story!

Myers is now occupied with disbursing the remaining Susan Sebastian Foundation funds to help the Vermont Respite House – the only one of its kind in Vermont, adding artwork to their patient rooms. The work continues even after Susan Sebastian and Elise Braun’s passing.

When so much bad is happening in the world, it is heartening to know that there are still many pockets of good.

Lasting Art, Part 2: Crossing the Finish Line

Shortly before Susan Sebastian died of a life-long illness, she had told her mother, Elise Braun, that she wanted original art placed in every room in every hospital in Vermont, so tired was she of looking at the bare walls. At the suggestion of Elise’s cousin, Alex Ryley, a New York City elder law attorney who had read Healing Spaces, she and Foundation Manager Gil Myers, used the book as an inspiration and guide for selecting art throughout the seven years of the project.

Elise Braun was too ill to attend the Art Center event. When I spoke (click HERE to watch the video), I thought she was listening via Skype, but it turned out the Skype connection failed. She had to wait until the day after the event to hear about it in person through Gil Myers and her friend, Deb Clark, a nurse. Both shared how happy Elise was to know that her work was complete. In Clarke’s words,

It was a treasured time (as Elise) listened, looked at photos, and asked questions with a smile from ear to ear.Braun said:

This final installation was the most celebrated. Bennington Hospital really outdid themselves. How great (it was that) people heard about Dr. Sternberg’s work that inspired Gil and me.Braun died peacefully just a few days later. Like a marathon runner, she had pushed herself through to the project’s finish.

When I heard of Elise Braun’s passing, I was reminded of one of my first patients when I was a young medical student. My patient who was near the end, seemed well enough when I bid her good-bye for the weekend, and told her that I would see her on Monday. She smiled quietly and said she was looking forward to seeing her son that weekend, and thought that this would be her final good-bye to me. When I returned on Monday, her bed was empty and the nurses told me that she had died quietly and at peace shortly after her son had visited. This was my first experience with a patient waiting to die until a loved one visited or a special event in their lives was accomplished – a wedding, a birth, a graduation.

Many healthcare professionals have had such experiences. I have had them in my own family. When my mother was dying of cancer, she waited for my aunt, who with my uncle were driving back to Montreal as fast as they could from their winter home in Florida. My mother had slipped into unconsciousness before they arrived and we all thought they would get there too late. But when my aunt – my mother’s sister, entered the hospital room, my mother raised herself up on the bed with all her strength and called out my aunt’s name. Then she slipped back into unconsciousness and died a few days later.

I couldn’t help but feel that Elise Braun waited for her life’s mission to be complete before allowing herself to slip away. Gil Myers and Deb Clark both thought that it was so. I would like to think that my words and my book played a small part in helping her to achieve that mission, which gave her a sense of peace and calm and fulfillment that her job was done.

That would be the greatest satisfaction any author could hope for.